An important source for family planning and health services, but what do we know about the clients they serve?

A call to involve important market actors to meet the health needs of family planning clients.

Photo: Elmvh/GFDL via Wikimedia Commons

The Sustainable Development Goals will be difficult to achieve without vigorous participation from the private sector. In fact, private drug shops and pharmacies are a widely-used source for health information, products, and services, including family planning (FP), especially in sub-Saharan Africa.1 Throughout Africa, however, the private sector is generally fragmented with little coordination, and regulatory oversight is not well understood and considered weak.2,3 These issues can hinder the ability of governments to ensure quality assurance for services and products that are delivered through private channels. In some contexts, these challenges are exacerbated by inherent tension between government and the private sector, with few incentives to promote quality of care. At the same time, a better understanding of supply-and-demand-side factors that prompt clients to use the private sector can shape policies, incentives, and public-private dialogue to involve the private sector in the overall health system.

Numerous studies have examined the feasibility and operational aspects (quality, access, use, and cost) of providing priority health interventions through drug shops and pharmacies.3–6 Others have analyzed contraceptive use patterns, market trends, and the role of the private sector in improving equity in access.7–9 Yet some gaps in knowledge about characteristics of clients who obtain their contraceptives from drug shops and pharmacies remains. Some key questions are: What do we know about this market segment? What patterns emerge from comparisons within and across countries? What differences do we see between countries with relatively high FP use compared with those with low FP use? While not all of these questions can be answered here, a deeper understanding of these clients can inform market-shaping policies and strategies aimed at working with the private sector to meet FP and other health needs.

FP is a relatively low-cost intervention with wide-ranging health, social, and economic benefits. Information on demographic and FP use patterns is readily available through Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS). Secondary analysis of DHS surveys in sub-Saharan Africa over the last 10 years was used in this brief to offer insights into the characteristics of FP clients who obtain contraceptives from private drug shops and pharmacies in selected countries.

The private provider landscape is diverse

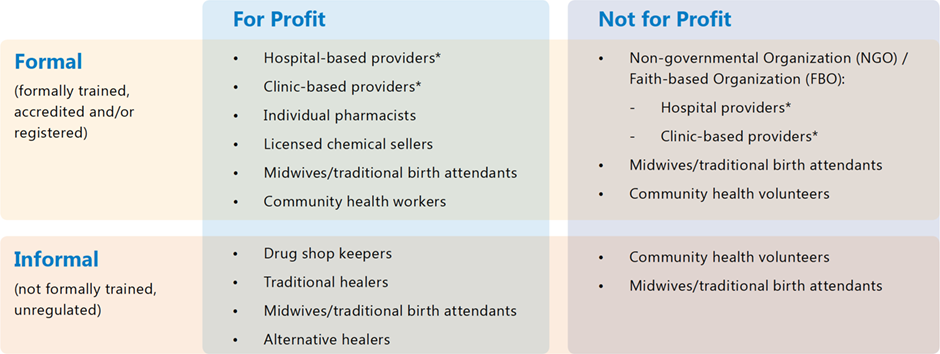

The private health sector is defined as all actors “who exist outside the public sector, whether their aim is philanthropic or commercial, and whose aim is to treat illness or prevent disease. The sector includes large and small commercial companies, groups of professionals such as doctors, national and international nongovernmental organizations, and individual providers, pharmacies, and shopkeepers.”10 Further, private health service providers can be categorized as informal or formal providers depending on how they are organized and whether they are accredited or registered with the government. However, these definitions are broad and diverse across the literature. Note that classifications var y across countries, and there is overlap. The table below provides a snapshot of terms.1,11,12

Table 1: Overview of private health sector providers

*providers = physicians, nurses, pharmacies, other

What do we know about the clients who source their contraceptives (including condoms) from pharmacies and drug shops?

Market segmentation analysis using DHS data reveals the important role of pharmacies and drug shops in providing contraceptive products.

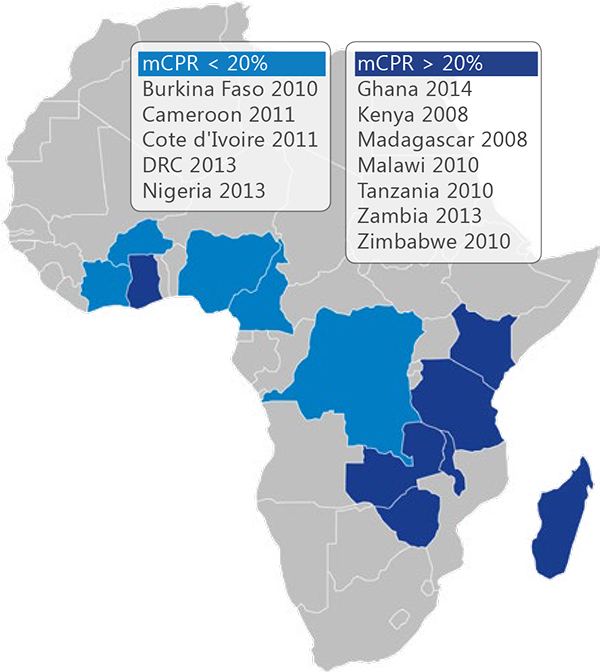

We examined selected countries in sub-Saharan Africa based on sample size and grouped them into two categories: low modern contraceptive prevalence rate (mCPR) (< 20%) and higher mCPR (> 20%) to identify any patterns across these categories. See the map to the left for a list of countries and year of the DHS survey used.

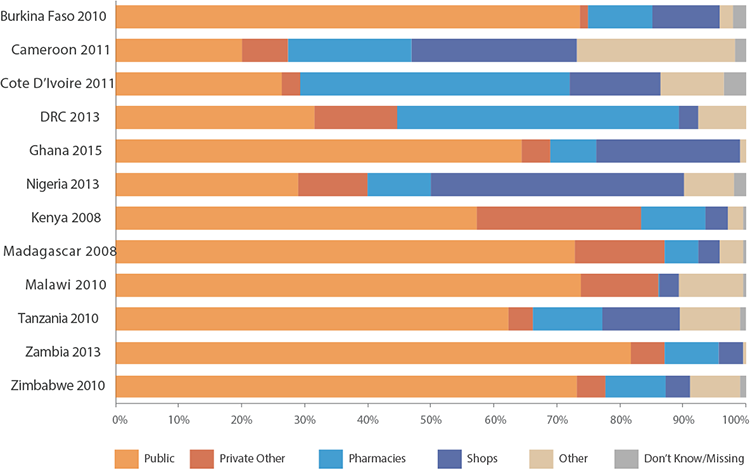

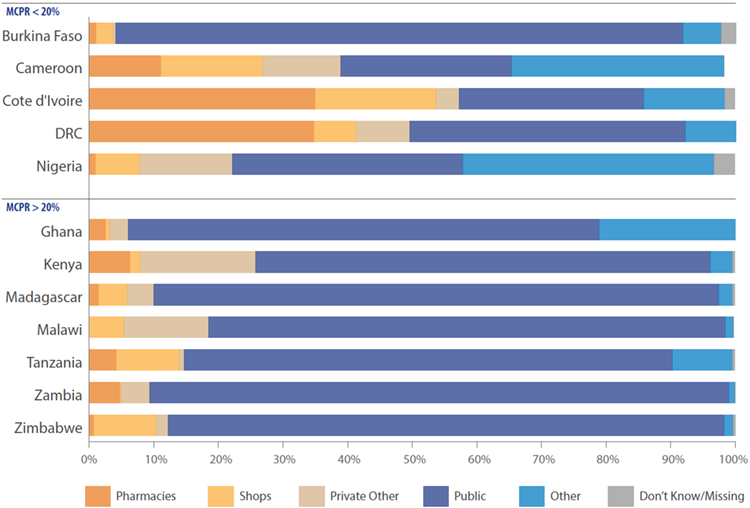

The majority of clients in low mCPR countries source contraception from private providers.

In Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi, and Madagascar, countries with a higher mCPR, over 70 percent of women last sourced their contraception from the public sector. In the majority of countries with mCPR of less than 20 percent, drug shops and pharmacies accounted for a large proportion of where women accessed their contraception, with the notable exception of Burkina Faso, where the public sector dominates as a source for FP. The use of pharmacies and drug shops was highest in Nigeria, Cote d’Ivoire, followed by the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Cameroon, where more than 40 percent of women obtained their contraceptive from a pharmacy or drug shop.

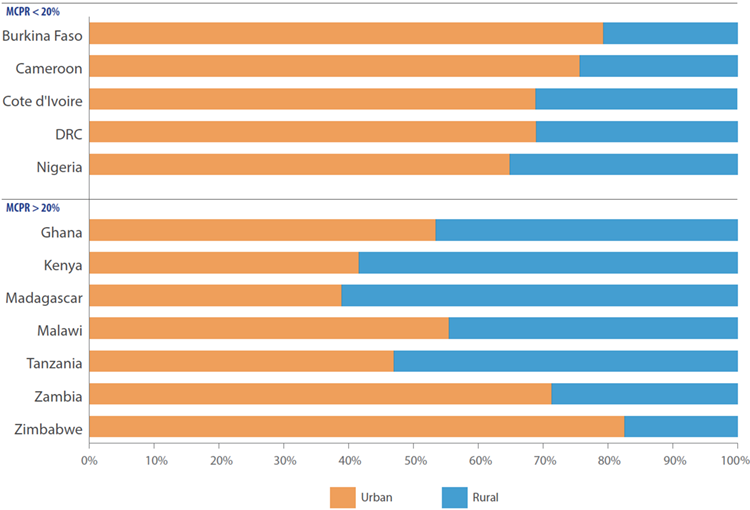

In 9 out of 12 countries, the majority of clients come from urban areas.

No major patterns emerge between lower mCPR (< 20 percent) and higher mCPR (> 20 percent) countries. In Zambia and Zimbabwe, more than 70 percent of women reside in urban areas, compared with Tanzania, Madagascar, and Kenya where the majority of women using pharmacies and shops are in rural areas.

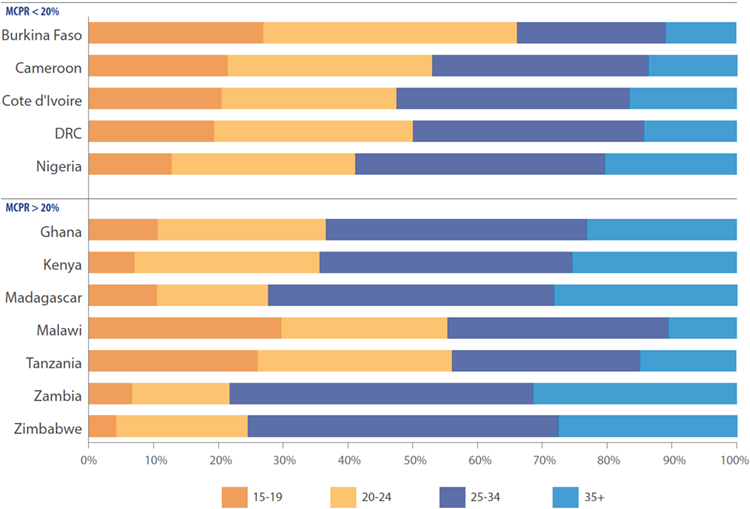

In low mCPR countries, over one-third of drug shop and pharmacy clients are youth.

In 5 out of 12 countries—Burkina Faso, Cameroon, the DRC, Malawi, and Tanzania—the majority of FP clients who obtained a contraceptive method from a pharmacy or shop were youth (ages 15 to 24). Among lower mCPR countries, over onethird of women who accessed contraception from a pharmacy or shop were youth. In higher mCPR countries, no general pattern was observed. Anecdotal and programmatic evidence suggests that young people often feel less comfortable going to established public clinics for contraception, versus the private sector which offers an additional advantage of privacy and anonymity. Youth are also most likely to prefer short acting methods such as condoms and pills that are more readily available in pharmacies and shops.

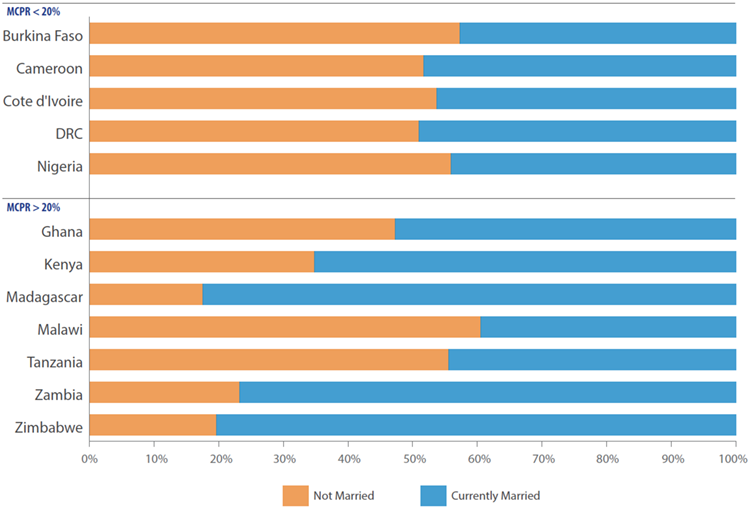

In low mCPR countries, over half of pharmacy or drug shop clients are unmarried.

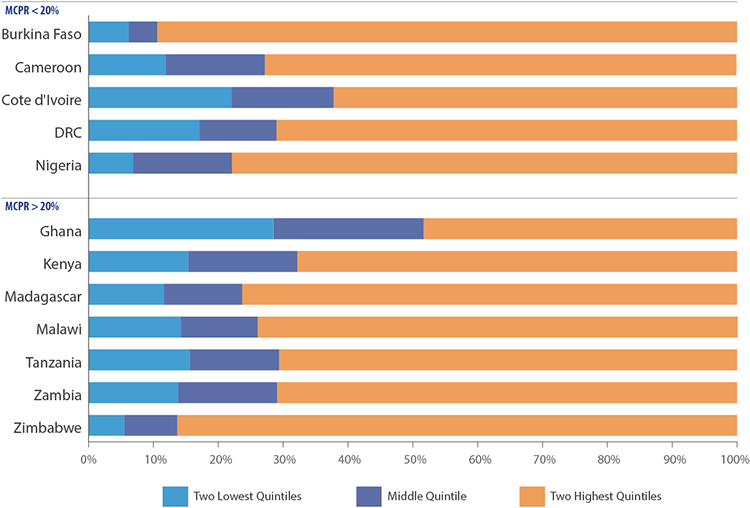

Drug shops and pharmacies for the most part serve relatively wealthy FP clients.

Yet, for the lowest two quintiles, drug shops & pharmacies are still an important source for FP.

What do these findings tell us?

In many contexts, drug shops and pharmacies are overlooked in program design, yet they are an important source for healthcare, particularly family planning. For example, youth can face stigma and other barriers when accessing FP in the public sector, yet young people ages 15 to 18 constitute a substantial proportion of those who seek contraceptives in drug shops and pharmacies. Similarly, single women, who may be stigmatized in traditional FP outlets, constitute a majority of the women who source their contraception in drug shops and pharmacies. At the same time, the majority of FP drug shop/pharmacy clients come from the top two wealth quintiles.

The information presented in this paper can offer insights for more targeted programming to expand quality and reach of FP and other health services through a variety of service delivery channels. Few African countries include pharmacies, much less drug shops, in their national health and FP strategies, yet these outlets already play an important role and could be further engaged to provide more and higher-quality services. Globally, the story is similar. WHO and other normative bodies that set the stage for country decision-making have placed little emphasis on the role of retail outlets as important FP sources. As a result, this vibrant sector is often ignored in planning by policymakers and program managers.

What can be done? Beyond better incorporation of drug shops and pharmacies into national health planning and international norms and standards, ministries of health, donors and implementing partners can:

1 Use market data to understand the respective roles of drug shops and pharmacies. Market research can provide useful insights into the type and range of health products and services offered through these channels, the motivations and behavioral drivers of their clients, and the relationship among public and private leaders and donors to design strategies that will improve quality, access to and financial sustainability of FP products and services.

2 Engage with relevant stakeholders in the public and private sector to understand how the strengths of each provider can be leveraged to meet client needs and develop strategies to reach underserved populations.

3 Identify options for retail providers to expand access to and quality of products and services; experiment with incentives for private providers and private-sector pharmacy associations to deliver high-quality services; and train retail providers to identify and eliminate fraudulent or fake drugs and improve the quality of services provided.

4 Determine and mitigate policy barriers to partnerships with drug shops and pharmacies. Liberalize provision of methods and brands through various cadres (following WHO medical eligibility criteria) and price reductions on high-quality commercial brands.

5 Define “success” measures for involving drug shops and pharmacists in reaching specific market segments and providing “backup” access to contraceptives when public sector delivery systems experience stockouts. Improve convenience and increase access to a range of contraceptive options through a total market approach.

6 Approach the above efforts through a perspective that recognizes the pharmacists and other trained private sector cadre can promote and educate women on a wide range of contraceptive methods to help improve access to information as well as choice.

Recommended Citation

Tanvi Pandit-Rajani, Nancy Harris, Leanne Dougherty, Emily Stammer, John Stanback, 2017, Drug Shops & Pharmacies A first stop for family planning and health ser vices, but what do we know about the clients they serve?, Arlington, VA: Advancing Partners & Communities.

References

1 Sudhinaraset M, Ingram M, Lofthouse HK, Montagu D. What Is the Role of Informal Healthcare Providers in Developing Countries? A Systematic Review. Derrick GE, editor. PLoS ONE. 2013 Feb 6;8(2):e54978.

2 Stanback J, Otterness C, Bekiita M, Nakayiza O, Mbonye AK. Injected with Controversy: Sales and Administration of Injectable Contraceptives in Uganda. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2011 Mar;37(01):024–9.

3 Wafula FN, Goodman CA. Are interventions for improving the quality of services provided by specialized drug shops effective in sub-Saharan Africa? A systematic review of the literature. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010 Aug 1;22(4):316–23.

4 Agha S, Do M. The quality of family planning services and client satisfaction in the public and private sectors in Kenya. Int J Qual Health Care. 2009 Apr 1;21(2):87–96.

5 Keesara SR, Juma PA, Harper CC. Why do women choose private over public facilities for family planning services? A qualitative study of post-partum women in an informal urban settlement in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2015 Dec [cited 2019 Mar 15];15(1).

6 Shah NM, Wang W, Bishai DM. Comparing private sector family planning services to government and NGO services in Ethiopia and Pakistan: how do social franchises compare across quality, equity and cost? Health Policy Plan. 2011 Jul 1;26(Suppl. 1):i63–71.

7 Hotchkiss DR, Godha D, Do M. Effect of an expansion in private sector provision of contraceptive supplies on horizontal inequity in modern contraceptive use: evidence from Africa and Asia. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10(1):33.

8 Campbell OMR, Benova L, Macleod D, Goodman C, Footman K, Pereira AL, et al. Who, What, Where: an analysis of private sector family planning provision in 57 low- and middle-income countries. Trop Med Int Health. 2015 Dec;20(12):1639–56

9 Agha S, Do M. Does an expansion in private sector contraceptive supply increase inequality in modern contraceptive use? Health Policy Plan. 2008 Aug 13;23(6):465–75.

10 Mills A, Brugha R, Hanson K, McPake B. What can be done about the private health sector in low-income countries? Bull World Health Organ. 2002;6.

11 Waters H. Working with the private sector for child health. Health Policy Plan. 2003 Jun 1;18(2):127–37.

12 Lagomarsino, Gina, Stefan Nachuk, and Sapna Singh Kundra. 2009. Public stewardship of private providers in mixed health systems: Synthesis report from the Rockefeller Foundation—sponsored initiative on the role of the private sector in health systems. Washington, DC: Results for Development Institute.