Introduction: Why Do We Care About Integration?

Photo: Dominic Chavez/World Bank

The idea of integrated services in development programming is not new. Within the health sector, the integration of family planning (FP) programs with other services has a long history. Most frequently, FP has been integrated with maternal and child health and HIV/STI services.1 The U.S. Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Bureau of Global Health has supported the integration of FP and reproductive health (RH), and reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health (RMNCH) into other health and non-health services for decades with projects such as Advance Africa, CATALYST, Extending Service Delivery, the Flexible Fund and Evidence to Action.2,3 These projects integrated RH/FP information into life-skills education programs; FP methods and counseling into community and hospital HIV counseling and testing and services to prevent mother-to-child transmission; FP into environmental programs; and leveraged FP services to improve socioeconomic development.

Integration has recently gained increased visibility. USAID’s Global Health Strategic Framework promotes an inclusive and integrated approach to global health.4 One of the key principles supporting the goal of Family Planning 2020 is the integration of FP within the continuum of care for women and children.5 Seventeen of the 2015 United Nations Sustainable Development Goals6 are related through a network of targets, promoting integration across various sectors.

There are two key reasons for integrating community-based FP with other health services. First, evidence from implementation studies shows that linking FP to other health and non-health services benefits clients and programs. For example, the provision of FP with maternal and child health services is associated with improved maternal and child health outcomes and economic development at the national level.7 Second, a favorable policy environment already exists in many countries, where policies mandate support for integrated community service delivery, especially in public-sector decentralized health systems. Of the 24 priority countries identified by the USAID’s Office of Population and Reproductive Health, 14 use integration as an approach to community health service delivery in their national policies, and three discuss integrated approaches without specifically using the term.8

Despite the significance of integration to well-functioning community-level service delivery and strong FP programs, there is a gap in documentation of the implementation process, outcomes, and added value. Through this brief, the Advancing Partners & Communities (APC) project documents its experience integrating FP into existing health and non-health projects implemented by seven grantees working in challenging environments in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, and provides insight about the added value of integration.

Defining Integration

APC’S Definitions of Integration

Full integration: the delivery of information or services at the same time in the same location. Activities are planned in coordination, delivered jointly by the same provider or a group of providers working in concert, and service-delivery data are collected jointly.

Partial integration: services offered at a different location or time. The program reaches the same members of the community, but the FP messages and information are delivered at a different location or time.

Integrated programming is currently defined in myriad ways, with no single generally accepted definition. Descriptions of integrated services may range from the functional “one-stop shop,”9 to the broader integration of health systems.10 The World Health Organization (WHO) defines integrated service delivery as “the organization and management of health services so that people get the care they need, when they need it, in ways that are user-friendly, achieve the desired results, and provide value for money.” Integrated health services can refer to multi-purpose service delivery points when a range of services for a catchment population is provided at one location and under one manager.11

The model adopted for this analysis describes integrated programming by the extent to which the new services are incorporated, as follows:12 1) programs that integrate FP education into existing services; 2) integrating FP education plus counseling on contraceptive methods; and 3) integrating education, counseling, and provision of contraceptives. Other models have been described, including one that classifies integration approaches into categories: referrals, community partnerships, service coordination (one-stop shopping), cross-training, and structural approaches for seamless services).1

What the Literature Tells Us About the Added Value of Integration

The prevailing evidence in peer-reviewed and grey literature suggests that integration can add value to existing programming.

Integration can introduce health services that may not be initially sought by the community. When health interventions for potentially sensitive topics like FP are integrated with less sensitive topics, such as child health or micro-finance, it is possible to reach wider populations with information and/or services they may not have sought otherwise in contexts familiar to them. Offering FP information and services to women during routine child immunization visits is effective because it is acceptable for clients and providers. As such, integration of FP into immunization services is recognized as a promising high-impact practice in FP.13 Economic development programs also provide opportunities to offer FP information and services to people who may otherwise not seek them.13,14,15

Integration improves the engagement of both sexes in activities, and has a particularly positive influence on male engagement. Pregnancy, childbirth, and newborn health interventions have better outcomes when men are involved because men can facilitate and support improved self-care of women, improved home care practices for the women and newborns, and improved use of skilled care during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal period for women and newborns. 16,17 Interventions that include men in FP have mainly achieved increases in knowledge and attitudes, but some have also led to increases in birth spacing and use of long-term contraceptives. 18 Evidence shows that integrated activities can minimize stigma about male involvement in sensitive subjects, which increases their participation. Exposing men to FP messages as part of a population, health, and environment (PHE) project allows couples to talk more freely about FP choices and seek services.19

Integration can generate demand for and increase uptake of essential health services by working across sectors and existing systems. A study in Ethiopia found that women who participated in an integrated FP and PHE program wanted fewer children than those who participated in the FP program alone, showing an increase in understanding of the relationship between family size and resource allocation.12 Generally, integration is a common approach to provide new services in the most remote and hardest-to-reach communities. Integration can be expedited through infrastructure and systems in place for delivering services such as maternal and child health (MCH) or HIV prevention, with modest investments to train staff and community health workers. The use of existing platforms facilitates quicker introduction and scale-up of essential services.1,12

Integration can reduce the costs of implementation, leading to more positive outcomes for reduced financial investment. A study examining the costs, cost efficiency, and cost effectiveness of integrating family planning with HIV care and treatment services found that although there were marginal costs associated with staff training and supervision and adoption of FP methods, integration was cost-efficient.20 With an initial investment, building upon existing systems, structures, and personnel results in net savings and stronger technical implementation.8,12

APC’s Approach to Integration

All APC integration projects worked in remote, low-resource areas characterized by extreme poverty, malnutrition, low contraceptive prevalence rates (CPR), high fertility rates, and unmet FP need. Organizations, geographic areas, existing programming, integration model, and approach are shown in Table 1.

Despite positive overall numbers in some countries, CPRs were considerably lower in the geographic areas where the APC projects operated. In Kenya’s Eastern Province, for example, only 10.7 percent of married women used any contraceptive method, compared to the overall country rate of 55.4 percent.21 The CPR in the Tanzania Kigoma Region’s Uvinza District was 14 percent compared to the national rate of 34.3 percent.22 In Uganda, the overall CPR is 26 percent, but in the Arua District of Uganda’s West Nile Region, it was 14.6 percent.23 CPR in Ethiopia is 33 percent,24 yet in the South Omo Zone pastoralist communities where the APC project operates, FP and child spacing concepts had not been introduced and services were non-existent.

Table 1. APC Grantee Organizations, Integration Models, and Integration Approaches

| ORGANIZATION | REGION/COUNTRY | EXISTING SERVICES | INTEGRATION MODEL12 |

ENTRY POINTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adventist Development & Relief Agency (ADRA) | Palpa, Rupandehi, Kapapilvastu Western Nepal | Economic development: sustainable agro-based livelihood & income diversification. Vocational & entrepreneurial classes | 1 | Women’s savings cooperatives, market centers |

| Global Team for Local Initiatives (GTLI) | South Omo Zone, Southern Nations People’s Region, Ethiopia | WASH, income generation: clean water access; hygiene, vocational literacy; organic composting, small scale gardening, chicken farming | 3 | Engaged emerging leaders of WASH and income generation as early adopters of FP |

| HealthRight International | Marakwet County, North Rift Valley Province, Kenya | RMNCH: improve quality, availability and acceptability of maternal and newborn care, increase adoption of healthy behaviors & care seeking | 3 | Tailored services across reproductive timeline from pre-conception to postpartum |

| Pathfinder International Tuungane project | Kigoma Region, Tanzania | PHE: land & fisheries management; sustainable agriculture, resource plans, community conservation microfinance banks | 3 | PHE FP/HTSP model households; outreach clinics; conservation, income generation & FP |

| WellShare International | Arua District, West Nile Region, Uganda | HIV: condom distribution; community outreach, BCC; youth-friendly services; counseling and referral to HIV testing and care services | 3 | Provided FP services during HIV community outreach, couples testing; PMTCT services |

| World Vision | Garba Tulla District, Isiolo County, Eastern Province, Kenya | MCH: community-based maternal, newborn, and child health (MNCH) antenatal care, child immunizations; involve men and religious leaders | 2 | Offered FP counseling to mothers visiting antenatal, postnatal, and immunization clinics |

| Salvation Army | East and Central Regions, Uganda | Vulnerable household: savings groups; farmer field schools; backyard gardening; HIV prevention mobilization; cooking demonstrations | 3 | Outreach and household visits; other vulnerable household services |

Data from routine monitoring and evaluation

APC partners implemented integration activities over an 18-month period (July 2014 through December 2015), collecting data through paper-based forms, country-owned management information systems, and surveys. APC used standard FP indicators, as well as several custom indicators, which varied by project and included:

- Number of acceptors new to modern contraception.

- Method mix.

- Couple years of protection (CYP).*

- Number of community health workers and/or other health providers trained or supported, by type of training.

- Number of community members reached with FP messages.

- Number of clients of reproductive age who received FP counseling.

- Number of clients who received FP services (and/or information) integrated into one or more other services at the same location and time.

* CYP is defined as the estimated protection provided by FP services during a one-year period, based upon the volume of all contraceptives sold or distributed free of charge to clients during that period. The CYP is calculated by multiplying the quantity of each method distributed to clients by a conversion factor to yield an estimate of the duration of contraceptive protection provided per unit of that method.

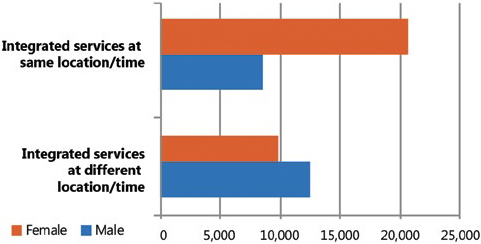

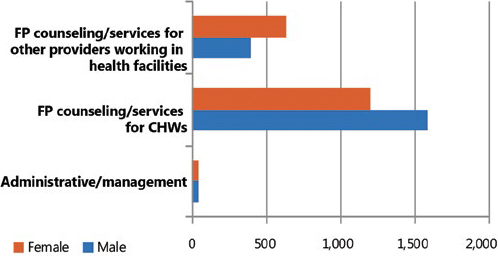

APC partner projects delivered integrated FP and existing services at the same location and time to more than 8,600 men and 20,600 women. Services targeting women were more likely to be fully integrated, whereas services targeting men were more often partially integrated (Figure 1). Partners provided FP capacity building and training—mostly counseling on methods and services to community health workers (CHWs), but also to facility-based health providers and administrators who supervised CHWs and linked them to health facilities and FP commodities (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Integration of Family Planning Services

Figure 2. CHWs and/or other health providers trained or supported, by bype of training

Overall, APC partners provided 95,612 CYP. Excluding male and female condoms, APC partners reached 47,335 acceptors new to modern contraception, 76 percent of whom sought long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods. (An additional 365,009 new acceptors of male and female condoms were reached through the HIV-prevention project). Table 2 shows method mix breakdown. Injectables were the preferred method, consistent with contraceptive choice preferences in sub-Saharan Africa.25 They were made accessible in large part by favorable policy environments and training CHWs to administer the injections. Implants were the second-most popular choice, followed by oral contraceptive pills.

Table 2. Distribution of Method Mix

| LARC | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Injectables | 19,811 | 41.9 |

| Implants | 9,887 | 20.9 |

| IUD | 5,700 | 12.0 |

| Female sterilization | 338 | 0.7 |

| Male sterilization | 100 | 0.2 |

| 35,836 | 76 | |

| Short-term methods | ||

| Oral contraceptive pills | 9,002 | 19.0 |

| Emergency contraception | 2,341 | 4.9 |

| Standard Days Method | 131 | 0.3 |

| Lactational amenorrhea | 25 | 0.1 |

| 11,499 | 24 | |

| Total all methods | 47,335 | |

Strategies that support effective integration

APC conducted a series of structured interviews with key informants to gather qualitative data about the experience of each organization and its clients. Based on quantitative and qualitative data, APC identified several strategies that seem to support effective integration of FP activities.

Use key entry points when designing integrated programs

Entry points are the conduits or instances at which the individual’s contact with the health system can facilitate access to new information and services. Certain health services are recognized as having potentially effective entry points for other services, as is the case with MCH and FP, and HIV and FP.26 APC grantees used a variety of entry points guided by opportunities that existing services could provide.

- ADRA used existing platforms—women’s cooperatives for economic development—to provide FP education in Nepal. Other entry points included market centers, market management committees, information corners, question boxes, and youth groups.

- GTLI filled a profound need by providing clean water and education on hygiene and sanitation to remote communities in Ethiopia. In addition, through livelihood activities such as chicken farming and gardening, women gained elevated status as they contributed to household assets and food security. Using WASH and income generation as gateways for community engagement, GTLI recruited emerging leaders as early adopters of FP.

- HealthRight used RNMCH clinic visits as opportunities to introduce FP to clients seeking antenatal and postnatal care in Kenya.

- Pathfinder’s Tuungane project, a PHE capacity-building in Tanzania, used model households for PHE, which adopted sustainable agriculture and resource planning, to also model FP and healthy timing and spacing of pregnancies (HTSP).

- WellShare International added FP services to community outreach for HIV couple testing and integrated FP services with existing PMTCT.

- World Vision offered counseling to all mothers who visited immunization, antenatal, and postnatal clinics on HTSP.

- The Salvation Army incorporated FP into household visits, community action teams, village savings and loan associations, farmer field schools, faith-based organizations, and youth clubs.

Design messages that reinforce the benefits of integration

Photo: Arne Hoel/World Bank

Key messages should emphasize the joint benefits of the integrated intervention. APC partners created linked, coordinated messages that highlighted the reciprocal relationship of its integrated activities.

- Pathfinder’s Tuungane project collaborated with local partners to develop messages. A tree planting analogy conveyed the importance of spacing children: just as there must be adequate space between trees when they are planted to allow roots to grow and support the weight of a fully grown tree, child spacing helps children thrive.

- ADRA weaved FP messages into its entrepreneurial education curriculum, highlighting the economic benefits of FP. The project used the phrase: “A managed family is a prosperous family,” to illustrate the link between planning and spacing of children, providing time for entrepreneurial activities, and the use of resources to send children to school and invest in an agricultural plot.

- GTLI focused on the importance of healthy children in pastoralist communities by linking clean water, nutrition, and child spacing to having more healthy children. These messages were part of a behavior change curriculum, with each message designed to build on another.

- HealthRight categorized and delivered approved ministry of health FP messages according to antenatal and postnatal time period to integrate FP into its RMNCH project in Kenya.

The community-based workforce reinforces activities and behavior

APC partners found that training various types or cadres of providers to offer comprehensive, integrated messaging and services reinforced integrated messaging.

- In addition to training facility-based staff and CHWs, ADRA worked with youth groups and community market management committees. Each group provided tailored FP messaging to target sub-populations with whom they work.

- GTLI used its own staff to conduct community outreach and train government health extension workers and teachers who focus on basic literacy and numeracy to provide services and integrated messages to their audiences.

- Tuungane trained government-managed forest scouts, beach management units, and CHWs to provide linked messaging about conservation and health outcomes and to refer community members to CHWs and health facilities for FP and other health services.

- The Salvation Army recruited and trained youth volunteers from a former project in Uganda to set up “youth corners” at health facilities to offer youth-oriented reproductive health services.

- World Vision’s mobile outreach clinics coordinated efforts of three different types of service providers: community health volunteers provided HTSP messages; community health extension workers provided counseling and short-acting contraceptives such as pills and condoms; and health workers treated minor illnesses such as diarrhea and skin infections.

Link with higher-level services, including health and non-health facilities

Harmonized messages, services, and referrals in communities and facilities institutionalize and magnify the positive effects of integration. All APC projects provided links to higher-level services for FP, and some provided links across health sectors.

- WellShare adapted forms for clients receiving FP and HIV services to allow cross-referral to providers at health facilities in Uganda. Community-level providers were prompted to refer for FP or HIV services, whatever the initial purpose of the encounter. Clients were then linked to providers at the health facility to streamline an integrated approach.

- HealthRight and World Vision, working in two different regions in Kenya, trained CHWs to provide integrated messages and services, and facility-level health providers to offer FP counseling during immunization, antenatal, and postnatal clinics.

Involve men and religious leaders

Just as integration can create entry points for sensitive subjects, it can increase the involvement of men and religious leaders. As important decision-makers in families and villages, men have much of the power but often scant understanding of the benefits of FP. It is well-accepted that engaging men in FP programs can dispel myths and reduce barriers and lead to improved health outcomes. Informed religious leaders can also be strong allies through their influence on entire communities.27

- World Vision found that when men were engaged in the integration project and approved of the concept of HTSP, mothers visited antenatal clinics more routinely, more women sought skilled delivery, and more women brought their children for immunization.

- World Vision also found that as a result of FP integration with MCH, religious leaders started discussing FP issues openly at mosques, which led the community to think more favorably about FP. Other leaders such as chief and clan elders embraced MCH messaging that included HTSP, and used community forums to spread the messages.

- HealthRight found that when FP was integrated into its maternal and newborn health project, male involvement increased. Anecdotally they found that men considered maternal and newborn health a familiar, non-controversial topic and a woman’s responsibility, while FP was a new subject that they wanted to challenge and discuss.

- The Salvation Army gained the support of the denomination’s pastors and trained them to incorporate FP into church messaging.

Create an enabling environment, including structural and policy change

Photo: Dominic Chavez/World Bank

Ensuring that community-based activities are sustainable is a key component of any project. One way to enhance sustainability of integrated programs is to harmonize structural and health system elements across various service delivery components, such as data collection forms and training materials, which often address individual health sectors separately.12,28

- Through advocacy at the sub-national level, HealthRight in Kenya adapted government data collection tools to include all FP methods and maternal and child health activities. While this is a step for creating an enabling environment for integrated service delivery, the forms do not connect to the national system.

Improving the structural and systematic environment for integrated services will take time and is difficult to achieve. It is essential for projects to be informed of existing policies that promote integration, and to participate in working groups, pay attention to links between services, and incorporate relevant structural and information system changes.

What Have We Learned, and What Have We Yet to Learn?

This analysis provides details on the design, techniques, and strategies used by APC grantees to integrate FP with a range of services—HIV and AIDS, MNCH, PHE, economic development, WASH, and sustainable development for vulnerable families. Working in remote, low-resource settings with low CPR represents the “last mile” in providing FP services. Integrated services have shown to be a positive force, both in terms of numbers of new acceptors generated and in the view of implementing grantees. This is encouraging and validates the community of practice emphasis on integrated programming.

Adding FP to an organization or project portfolio can increase commitment to providing essential health services. Five of seven APC projects stated that their integration project increased commitment to FP or integrated approaches. Most grantees indicated that integrated programming would continue in some way, having been incorporated into strategic plans and CHW job descriptions. Pathfinder’s Tuungane will continue with support from the mission in Tanzania. World Vision and GTLI will continue with APC funding.

The evaluation of integration projects is difficult. There is no standard measurement and most integrated projects are highly contextualized to individual communities and countries. Additionally, many projects—including APC—are not evaluated from a holistic perspective. Funders, projects, and governments should create a common language for integrated approaches and systematically document their added value. Ideally, evaluations should be planned at the beginning of the project and document the reciprocal impact that integration has on each program component.

Cost-effectiveness is believed to be one of the biggest benefits of integration, yet it is not well documented in the literature. While formal cost analyses were not conducted, APC projects reported some cost savings as a result of implementing the integration projects. One project estimated that an integrated project cost 25 percent less than stand-alone projects, and produced equal-to-better results. Funders or implementers should undertake cost analyses whenever possible.

References

1 Sebert Kuhlmann, A., Gavin, L, Galavotti, C. (2010). The Integration of Family Planning with Other Health Services: A literature review. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 36(4), 189–196.

2 Bitar, S., Lamborne, M. (January 2014). ![]() Uganda improvement collaborative: Integration of family planning into maternal and neonatal health programming (Technical brief). Washington, DC: Evidence to Action Project.

Uganda improvement collaborative: Integration of family planning into maternal and neonatal health programming (Technical brief). Washington, DC: Evidence to Action Project.

3 Ringheim, K. C., Boswell, L., Elliott, L., Ryan, L., Graham, V. (May 2013). ![]() USAID Flexible Fund: 10-year program learning document. Calverton, MD: ICF International.

USAID Flexible Fund: 10-year program learning document. Calverton, MD: ICF International.

4 USAID’s Global Health Strategic Framework.(2013, November 22).

5 What we do. (2016).

6 Le Blanc, D. (March 2015). ![]() Towards integration at last? The sustainable development goals as a network of targets (DESA Working Paper No. 141 ST/ESA/2015/DWP/141). New York, NY. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

Towards integration at last? The sustainable development goals as a network of targets (DESA Working Paper No. 141 ST/ESA/2015/DWP/141). New York, NY. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

7 Ringheim, K., Gribble, J., Foreman, M. (August 2011). Integrating family planning and maternal and child health care: Saving lives, money, and time (Policy brief). Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau.

8 Community Health Systems Catalog.

9 Foreit, K., Hardee, K., Agarwal, K. (2002). When Does It Make Sense to Consider Integrating STI and HIV Services with Family Planning Services? International Family Planning Perspectives, 28(2), 105–107.

10 Briggs, C. J., Garner, P. (2006). Strategies for integrating primary health services in middle- and low-income countries at the point of delivery. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews (2): CD003318.

11 World Health Organization (May 2008). ![]() Integrated health services - what and why. (Technical Brief No.1).

Integrated health services - what and why. (Technical Brief No.1).

12 Borwankar, R., Amieva, S. (2015). Desk Review of Programs Integrating Family Planning with Food Security and Nutrition. Washington, DC: FHI 360/FANTA.

13 High-Impact Practices in Family Planning (HIP). (July 2013) Family planning and immunization integration: Reaching postpartum women with family planning services. Washington, DC: USAID; 2013 Jul.

14 Yavinsky, R. W., Lamere, C., Patterson, K. P., Bremner, J. (2015). The impact of population, health, and environment projects: A synthesis of evidence (Working Paper). Washington, DC: Population Council, The Evidence Project.

15 Harris, N., Orobaton, N., Smith, J., Marrkand, J. Linking Financial Inclusion and Family Planning Programs. Presentation at the International Conference on Family Planning Nosa Dua, January, 2016.

16 World Health Organization. WHO recommendations on health promotion interventions for maternal and newborn health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

17 Davis J., Vyankandondera J., Luchters S., Simon D., Holmes W. (2016). Male involvement in reproductive, maternal and child health: a qualitative study of policymaker and practitioner perspectives in the Pacific. Reprod Health, 13(1): 81. doi: 10.1186/s12978-016-0184-2.

18 Rottach E, Schuler SR, Hardee K. (2009). ![]() Gender perspectives improve reproductive health outcomes: New evidence. Washington, DC: USAID and Population Reference Bureau.

Gender perspectives improve reproductive health outcomes: New evidence. Washington, DC: USAID and Population Reference Bureau.

19 FHI 360 ![]() Integrating family planning into other development sectors (2013).

Integrating family planning into other development sectors (2013).

20 Shade, S.B., Kevany, S., Onono, M., Ochieng, G., Steinfeld, R.L., Grossman, D., Newmann, S.J., Blat, C., Bukusi, E.A., Cohen, C.R. (October 2013). Cost, cost-efficiency and cost-effectiveness of integrated family planning and HIV services. AIDS, 27 (Suppl 1):S87–92.

21 ![]() PMA2014/Kenya, Performance, Monitoring & Accountability 2020. (2014).

PMA2014/Kenya, Performance, Monitoring & Accountability 2020. (2014).

22 The World Bank. (December 2011). ![]() Reproductive health at a glance - Tanzania.

Reproductive health at a glance - Tanzania.

23 Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and ICF International Inc. 2012. Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2011. Kampala, Uganda: UBOS and Calverton, Maryland: ICF International Inc.

24 ![]() PMA 2014/Ethiopia, Performance, Monitoring & Accountability 2020. (2014).

PMA 2014/Ethiopia, Performance, Monitoring & Accountability 2020. (2014).

25 Seiber, E.E., Bertrand, J.T., Sullivan, T.M. (September 2007). Changes in contraceptive method mix In developing countries. International Family Planning Perspectives, 33(3), 117–123.

26 Farrell B., L. (2007). ![]() Family planning-integrated HIV services: A framework for integrating family planning and antiretroviral therapy services. New York: EngenderHealth/The ACQUIRE Project.

Family planning-integrated HIV services: A framework for integrating family planning and antiretroviral therapy services. New York: EngenderHealth/The ACQUIRE Project.

27 Christian Connections for International Health. (2012). Family Planning Critical to Church Role in Health Care: Voices from the Global South Series.

28 Johnson, K., Varallyay, I., Ametepi, P. (2012). Integration of HIV and Family Planning Health Services in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of the Literature, Current Recommendations, and Evidence from the Service Provision Assessment Health Facility Surveys (DHS Analytical Studies No. 30). Calverton, Maryland, USA: ICF International.

Recommended Citation

Myriam Hamdallah, Hannah Foehringer Merchant, Elizabeth Creel and Nancy Harris. 2017. The Added Value of Integrating Family Planning into Community-based Services: Learning from Implementation. Arlington, VA: Advancing Partners & Communities.