Background

Sierra Leone is one of three West African countries to have experienced the devastating Ebola outbreak of 2014–16, which resulted in the deaths of almost 4,000 individuals and the largest group of Ebola survivors in history. In the immediate post-emergency period, the Government of Sierra Leone recognized that those who had survived the virus were particularly vulnerable to ongoing health, economic, and social challenges.

Given the unprecedented situation at that time—more than 3,400 Ebola virus disease (EVD) survivors, the death of 221 medical professionals from Ebola,1 and an already fragile health system—the government and its partners needed to respond to the immediate needs of survivors.

In November 2015, the Government established the Comprehensive Program for Ebola Survivors (CPES) as part of the ‘Resilient Zero’ pillar of the president’s 10–24 month post-Ebola recovery priorities. Survivors were also included in the existing Free Health Care Initiative (FHCI) program, already offered to children under 5 and pregnant and lactating women, which allowed survivors to access public-sector health services without cost.

Interventions

CPES Phase 1

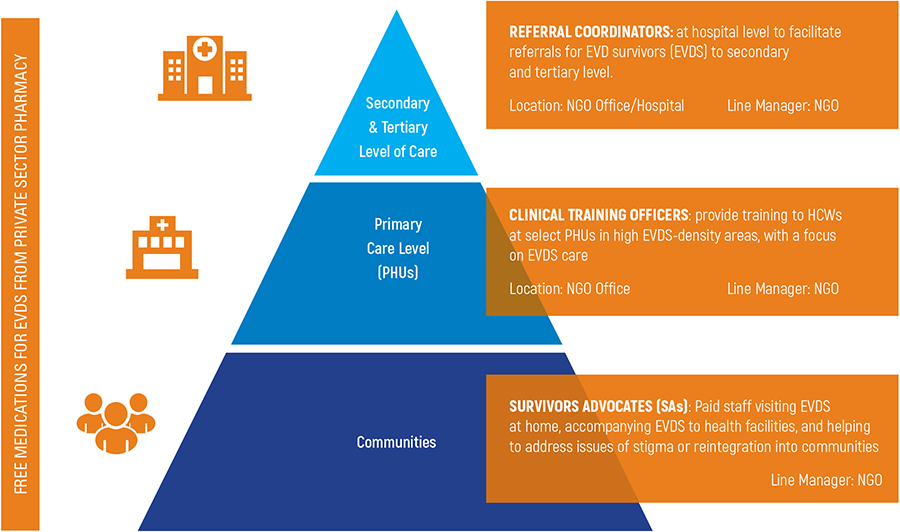

The CPES program included interventions at the community, primary, secondary, and tertiary levels to meet EVD survivors’ health and social needs, in addition to their objective of maintaining zero new cases of EVD. The CPES program was initially supported technically and financially by DfID, WHO, and USAID, and was implemented by eight NGO partners2 in 13 of the 14 districts, with government oversight from an inter-ministerial program implementation unit (PIU). As the country’s already fragile health system had been devastated by the outbreak, these partners invested heavily in medicines, surveillance, and human resources capacity building. The CPES support structure and many of these interventions operated largely outside the country’s public health care structures (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: CPES Phase 1 – Program Intervention and Human Resources

While these interventions sought to restore the public’s confidence in the health system, the program also created unrealistic expectations about what could be sustained in the long term on behalf of survivors, and inadvertently, this approach also increased stigmatization.

At the end of CPES Phase 13, assessment feedback received by the Ministry of Health and Sanitation (MOHS) suggested that the program needed to be more aligned with MOHS priorities, including the FHCI, the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response program, and the National Community Health Worker (CHW) program. This was coupled with recognition, determined through program supervision, that many survivor health issues-mental health, eye complications, etc.-were relevant to other vulnerable groups as well.

Referral Coordinators (18):

Who: CHOs and nurses

Role: Facilitate incoming and outgoing referrals at secondary and tertiary levels of care facilities for all FHCI categories; support hospital management in the use of data for decision making

Location: 1 in each district hospital (14) and referral hospitals (4) under line management of hospital superintendent and/or hospital matron

CPES Phase 2

Using lessons learned from Phase 1, and recognizing the need to bring survivor care into the FHCI to ensure sustainability, the MOHS agreed to transition CPES from an NGO partner-led program to a more integrated program within national and district MOHS structures, and to consider formerly incorporating key HR positions created during Phase 1.

Phase 2, which began in October 2017, was supported largely by the USAID-funded Advancing Partners & Communities project. A key strategy during this phase was to shift the mindset of those involved in the Ebola outbreak from emergency to a longer-term sustainable response, while recognizing the ongoing needs of Ebola survivors and emphasizing self-reliance and system strengthening.

Another key aspect of Phase 2 was adapting and transitioning the successes of Phase 1 into existing health sector structures, especially at the district level. Two roles from the CPES Phase 1 program were identified by the MOHS as particularly valuable: the clinical training officer (CTO) and the referral coordinator (RC).

Clinical Training Officers (14):

Who: Community health officers (CHOs)

Role: Provide clinical and non-clinical mentorship to HCWs on FHCI categories related health issues, and support DHMTs to use data for decision making

Location: 1 in each district under line management of DHMT

Target: ~20 facilities in each district chosen along with DHMT based on key health indicator, i.e., maternal mortality

At the same time, several interventions were prioritized during the transition phase: 1) integrating the survivor advocates (SA) into the national CHW program; 2) including EVD survival data into the MOHS’ health management information system, and; 3) extending the CPES program’s mandate to include all FHCI categories (pregnant women, lactating mothers, and children under 5-years) as beneficiaries.

As noted, the transition focused on promoting the integration of the CTO and RC roles into the district and hospital management structures, respectively. The 32 CTOs and RCs, previously hired and managed by various partner organizations, were placed under the direct management of the district health management teams (DHMTs) and government hospitals, respectively.

In transitioning from a survivor-focused program to one that focused on the broader FHCI population, the program also moved to support the entire country instead of targeting the districts and health facilities with high EVD survivor density. This was a significant programmatic shift, as it required moving from a target population of less than 10,000 to roughly 1.8 million people (all FHCI categories).

During Phase 2, CTOs and RCs received additional capacity-building, mentorship, and operational support to ensure they were ready to assume their expanded responsibilities. CTOs were trained on FHCI population-related issues, especially maternal and child health, and mentorship to strengthen their capacity to work with health care workers (HCWs). They also received tools such as human body charts that enhanced their one-on-one sessions with HCWs.

Using the human body chart strengthens the effectiveness of CTO mentorship. With this visual aid, CTOs are able to better interact with health care workers.

RCs received in-depth training and mentorship on tools designed to collect information on incoming and outgoing referrals. They were also trained to strengthen referral pathways in their districts and record bed capacity at hospitals, which helped the hospitals manage patient intake.

Overall, Phase 2 has allowed the MOHS, through the CPES PIU, to lead the management, oversight, and evaluation of the daily work of the CTOs and RCs as well as their relationships with their line managers in the DHMTs and hospitals.

The CPES PIU also prioritized the transfer of community health responsibilities covered by SAs (who had an essential role as peer support workers during the acute phase of the Ebola outbreak) to CHWs. In turn, CHWs have been trained to identify the special needs of survivors in their communities; refer them to the appropriate health facility in each district; and lead advocacy efforts to integrate them into the FHCI to ensure access to free medications and services.

Results

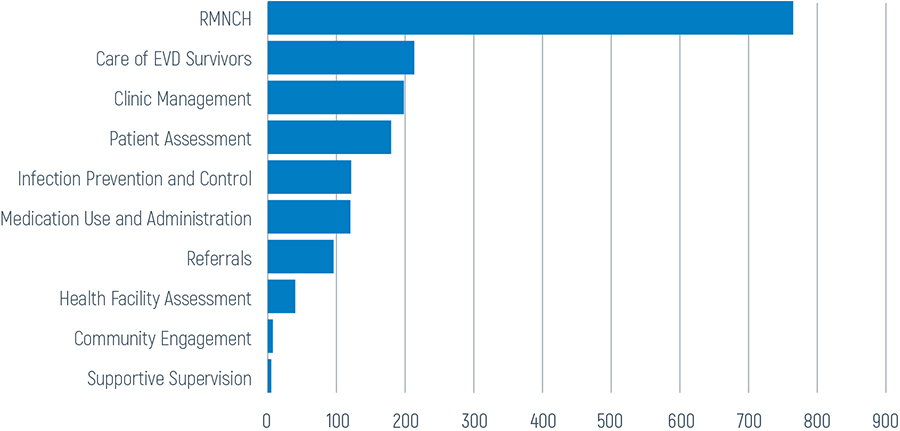

Figure 2: Results of Mentorship Sessions (October 2017 - August 2018, N=1749)

Yokie works with the pharmacist and other health care workers at Connaught Hospital to ensure that FHCI referral patients have access to free health care services and drugs.

Since Phase 2 began, Sierra Leone’s CTOs and RCs have supported the strengthening of health service delivery in their districts. CTOs conducted almost 2,000 visits to 264 primary health units across the country. As shown in Figure 2, the three major topics covered during their mentorship sessions with HCWs were maternal health, patient assessment, and EVD survivor care.

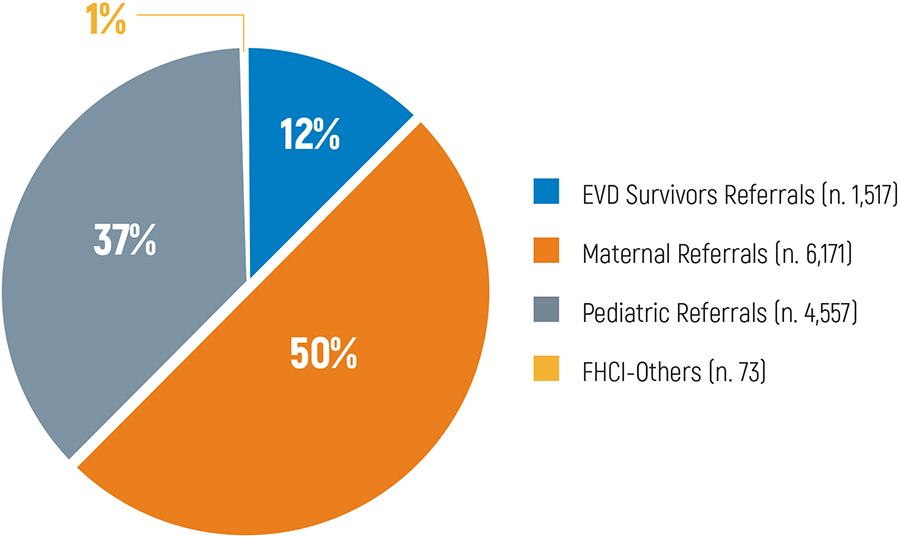

In the same period, RCs have facilitated and recorded more than 12,000 referrals. Pregnant and lactating mothers are the FHCI groups with the highest number of referrals (see Figure 3).

In Phase 2, the program also supported monthly reporting to the DHMTs and district hospitals to increase use of data for decision making. This has provided line managers with direct information about activities conducted at the district level by the two cadres, as well as important data in terms of referrals (i.e., origin, causes, and outcomes), allowing hospitals and DHMTs to easily identify whether additional mentorship is needed.

Figure 3: Referrals Supported by the Program, October 2017 - August 2018 (N. 12,318)

Lessons and Recommendations

Considering how much the country’s health system was disrupted by the Ebola outbreak, initiating a program running primarily outside the formal health structure to respond to EVDS needs seemed logical at the time.

However, after 15 months of implementation, it was clear to most that the program as it was designed was not sustainable.

With the progressive improvement in the health status of survivors, the implementation of the CPES Phase 2 program highlighted the following key lessons:

Integration

Community Health Worker Peer Supervisors in Western Area Urban participated in a training to recognize health care needs for EVDS survivors and people with mental health conditions.

- Challenges with the quality of health service delivery are beyond the specific needs of Ebola survivors. Therefore, a) the MOHS welcomed CTO mentorship efforts to respond to broader vulnerable-population health issues; and b) national integration of services for survivors into MOHS mainstream services was needed.

- The referral system that was established improved access to specialized care for Ebola survivors and was later extended to all FHCI groups.

Transition

- The peer-to-peer approach implemented with the SAs helped reduce stigma associated with EVD and supported the rebuilding of trust between survivors, their communities, and local health facilities. However, the transition from SAs to CHWs should have been initiated earlier to avoid community-level gaps in coverage.

- The integration of CTOs and RCs into the district health structure was well received by DHMTs. However, an earlier transition would have improved the integration of these two cadres into MOHS structures.

Our main recommendation for a similar post-outbreak context would be for government and implementing partners to consider key interventions for the sustainability of services and exit strategies during the program design phase. This would allow a more comprehensive response to gaps in the health system through the design of a range of interventions that are aimed at meeting both short- and long-term needs of the specific populations as well as the country as a whole.

1 MOHS, Ministry of Social Welfare and Children’s Affairs DPC – PS Database

2 GOAL International (management lead), Partners in Health (technical lead), International Medical Corps, King’s Sierra Leone Partnership, Medicos del Mundo, Save the Children, Welbodi Partnership, and World Hope International

3 April 2016–September 2017